Currently reading

A Marvelous Quartet

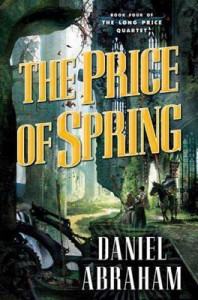

The Price of Spring concludes what is now one of my all-time favorite fantasy epics, The Long Price Quartet. Daniel Abraham not only continues his masterful sentence-by-sentence writing, with its vivid descriptions and telling dialogue, but he also maintains the vision that made book 1 (A Shadow in Summer) so compelling. The sweeping ramifications of intimate decisions come to the fore once more in this final volume, reflecting the close-in focus of the first volume. All the things done and suffered by our core characters (Otah, Maati, Eiah, and Idaan chief among them) tie into one theme or another and have significance for the development of the plot. Generally speaking, this is close-knit writing, and its tapestry is a work of wonder.

Being a great lover of theme even above character and plot, I was most impressed with how Abraham bound up every thread of this novel with the main themes of the series. One can surmise from the book titles that the passing of the seasons is the major theme ruling all other themes in this series. The Price of Spring unites the concepts of andat (a living idea) with the passing of the seasons to reflect on the timeless truths of the cycle of life, death, and rebirth. No profound revelation is made, but this old truth is resonant and Abraham employs all the best tools of a sensitive writer in all the best ways, so that the final product is a work of beauty and poetry.

Advice to readers: follow the motif of the flower. It appears at least in A Betrayal in Winter (prologue chapter), An Autumn War (one of the final chapters, as well as one of the middle chapters in which Otah launches a doomed assault), and in the epilogue chapter of The Price of Spring. It may have been present in A Shadow in Summer but I missed it since it didn't seem so important at the time. I'd like to elaborate just a bit, so the paragraph that follows will be a SPOILER. Also, apologies if my thoughts are somewhat disjointed below, since the overall tapestry is so delicately woven with an impressively multivalent depth. There is so much symbolic intricacy to ponder that it boggles the mind, and one struggles to subject it to rigorous analysis.

BEGIN SPOILER.

The prologue chapter of A Betrayal in Winter describes a white flower blooming in the courtyard of the Khai's palace in Machi. The flower is spattered with blood, the red standing out against the whiteness of the flower as well as the whiteness of the snow lingering from winter. Spring is just beginning. The end of A Betrayal in Winter sees Otah victorious against his scheming and murderous sister Idaan, who tried to become a Khai by murdering her brothers. She murdered Danat but did not succeed against Otah. Otah is now Khai but pardons his sister, sending her into exile instead of executing her. At the end of the novel, she is walking into the distance across the autumn snows, standing out red against the whiteness of the snow. At the end of An Autumn War, after the devastating war of Balasar Gice against the Khaiem and Maati's shattering mistake of unleashing the andat Seedless's new form, Maati goes into exile in a remote cave in the autumn. Seedless had caused infertility in the men of Galt and the women of the Khaiem. Maati's protégé Eiah nevertheless forgives Maati's mistake and brings him flowers colored orange and yellow -- colors representing both autumn and the city of Machi. It is a reminder of the tragic fall of Machi but also a symbol that there may be hope. Finally, at the end of The Price of Spring, Otah's son Danat (named after his brother who had been slain by Idaan), delivers a funeral eulogy for Otah, speaking of the flower as a metaphor for the passing of seasons both in nature and in human life. He stresses a distinction (using language reminiscent of the old poets when discussing the binding of an andat) between returning and replacement. As Otah himself had realized in the letters he had written to his dead wife, no one ever returns when the springtimes of life come around. Each person, as each flower, dies; but he is replaced in one way or another. With this eulogy, the new Danat marks a new age of mankind, one free from the powers of the andat (with all the possible death implied by that...), and one hopefully also free of the internecine strife of the old Khaiate ways. Note that "Danat" is an anagram of "andat". As each andat newly bound is a variation on an older version of its theme, so too is Otah's son Danat a variation on the uncle that was killed by Idaan; or, perhaps it is better to say that he represents a replacement of the previous generation rather than the old Danat in particular. He won't follow the same path, but he is a nod to the past, and he is Otah's creation, as the andat were the creations of poets. Danat is Otah's instrument for change and the betterment of humanity. Also, just as andat are representations of an idea, summoned by a poetic incantation, so too does Danat speak poetically in the eulogy about springtime. The price of spring was bloodshed, as blood sullied the white flower in Machi's courtyard. The price of spring is also the potential for bloodshed, now that the world is left free of the andat's oppressive enforcement of peace. Peace among the nations is no longer guaranteed. Spring is that time when life is renewed and the military campaign season begins. The new age of the world reflects this co-habitation of life and death.

END SPOILER.

So, the gist of my review is this: The Long Price Quartet is a masterpiece. I've mentioned in my previous reviews that sometimes there is too much introspection on the part of the characters. This remains my opinion, but it is forgivable because it is not really intrusive. And indeed, being of a more thematic bent myself, I may have overlooked some of the intricacies of character development that these introspections evoke. The way that Daniel Abraham wields symbolism as a narrative tool impressed me like few authors have before. In this respect, he approaches the mastery that Gene Wolfe so effortlessly displays. I am happy that, by the end of this series, my initial Wolfean impression remains. If Wolfe is an idea (or ideal!), then Abraham is a new Wolfean andat, transmitting the core element of symbolic mastery while establishing idiosyncrasies of his own.

2

2